- Home

- BLOG & STORIES

BLOG & STORIES

Drug Primer: MDPHP

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Jan 19, 2026 | Drug Classes

By Kevin Shanks, D-ABFT-FT

Stimulants come and go. New ones arrive on the illicit drug market all the time. One of the newest stimulants to be identified is MDPHP, also known as 3′,4′-Methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinohexiophenone. It is a substituted cathinone, a class of compounds related to cathinone, a naturally occurring stimulant alkaloid found in the plant Catha edulus (khat). MDPHP belongs to the pyrrolidinophenone subclass and is structurally related to older stimulant compounds, alpha-PVP and MDPV. MDPHP first appeared on world drug markets around 2014-2015, but has recently seen an increase in prevalence. While not explicitly listed as a controlled substance in the United States, it may be considered a positional isomer of the already controlled MDPV and alpha-PVP, and therefore be considered illegal to manufacture, possess, distribute, and consume.

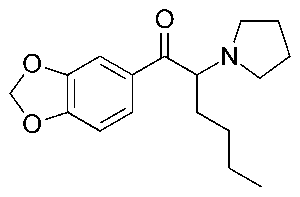

Chemical Structure of MDPHP drawn by Kevin G. Shanks (2026)

Pharmacologically, the substituted cathinones class primarily acts on monoamine transporters in the body and inhibits the reuptake of dopamine, norepinephrine, and/or serotonin and may act as releasers of any of the three neurotransmitters. MDPHP acts primarily as a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. The end result of this action is an increased concentration of neurotransmitters in the nerve cell synapse, which leads to stimulant physiological effects on the body. People who use stimulants are typically seeking the desired effects such as euphoria, increased energy, sociability, and alertness. But adverse effects include anxiety, agitation, paranoia, hallucinations, and aggression. When taken in overdose, acute toxicity is demonstrated via hypertension, hyperthermia, tachycardia, severe agitation, hallucinations, seizure, kidney failure, rhabdomyolysis, and death. Chronic use can manifest in cognitive impairment, sleepiness/tiredness, psychosis, physical and psychological dependence and addiction.

MDPHP has been implicated in fatalities in peer-reviewed published literature. In one case published by Di Candia et al., a 48 year old male with back and leg pain was found semi-unconscious on a public street. Emergency personnel were called and they documented history to include an HIV+ status and amnesia. After arrival at the hospital, his breathing and heart rate increased and he became unconscious before respiratory and cardiac activity stopped and could not be regained. At autopsy, various bone fractures, cerebral and pulmonary congestion and edema, and atrial and ventricular hemorrhages were documented. Toxicological analysis of postmortem femoral blood was positive for MDPHP (399 ng/mL).

In a second case published by Croce et al. a 30 year old male with a history of drug use and addiction was found deceased in his bedroom. He was last seen alive 24 hours prior to discovery. At autopsy, pleural visceral congestion, pulmonary edema, and moderate hepatic steatosis were observed. Toxicological analysis was completed on postmortem central blood and peripheral blood, among other specimens drawn at autopsy. MDPHP was positive in the central blood (1,639.99 ng/mL) and in the peripheral blood (1,601.90 ng/mL).

In a third case published by Casati et al. a 58 year old male was found floating in the water. He was last seen alive 7 days prior. Documented medical history included HIV+ status and he regularly used MDPV. At autopsy, rigor was present. Both hands were macerated and the heart was enlarged with mild ventricular hypertrophy. Cerebral and pulmonary congestion were also observed. Toxicological analysis was positive for MDPHP in femoral blood (350 ng/mL) and central blood (110 ng/mL). Other substances present included MDPV, MDPPP, MDPBP, citalopram, clonazepam, and 7-aminoclonazepam.

As a new stimulant, it is prudent to be aware of MDPHP and its availability on the illicit drug market. Axis monitors MDPHP in the Novel Emerging Compounds (NEC) panel (order code 13710) and Comprehensive Panel, Blood with Analyte Assurance (order code 70510) using liquid chromatography with quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (LC-QToF-MS).

If you have questions about MDPHP and how it may play a role in your medical-legal investigation, please reach out to subject matter experts by email ([email protected]) or phone (317-759-4869, Option 3).

References

- Di Candia, D., Boracchi, M., Ciprandi, B. et al. (2022) A unique case of death by MDPHP with no other co-ingestion: a forensic toxicology case. International Journal of Legal Medicine. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-022-02799-w

- Croce, E.B., Dimitrova, A., Grazia Di Mili, M. et al. (2025) Postmortem distribution of MDPHP in a fatal intoxication case. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkae092

- Casati, S., Ravelli, A., Dei Cas, M. et al. (2025) Polydrug fatal intoxication involving MDPHP: Detection and in silico investigation of multiple 3,4-methylenedioxy-derived designer drugs and their metabolites. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkaf048

Drug Primer: Diphenidine

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Jan 9, 2026 | Drug Classes

By Stuart Kurtz, D-ABFT-FT

Drug Primer: Diphenidine

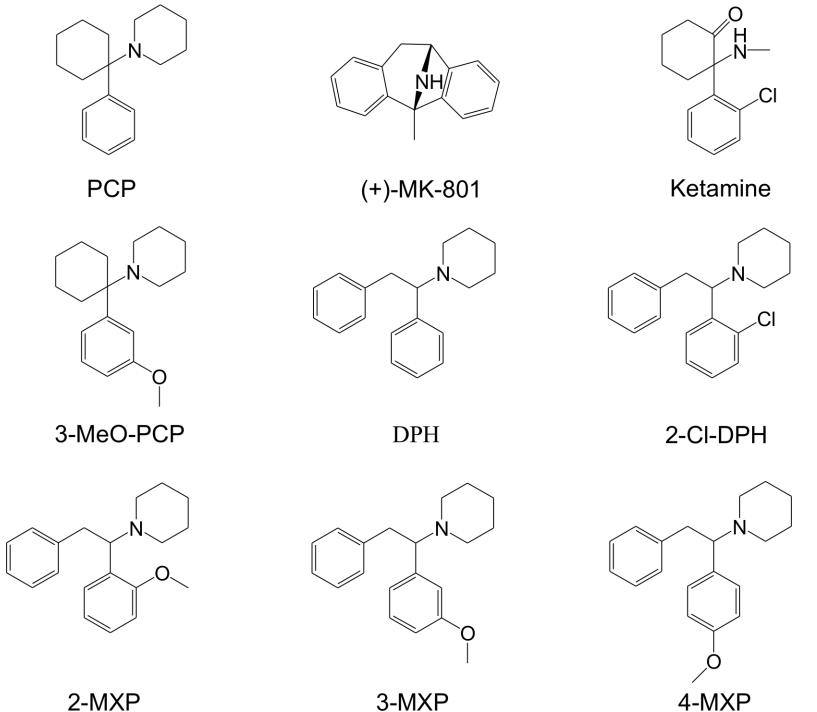

1-(1,2-diphenylethyl)piperidine, commonly known as diphenidine, is part of the 1,2-diarylethylamine class. This class includes drugs such as phencyclidine (PCP), 3-methoxyphencyclidine (3-MeO-PCP), and ketamine. These compounds can interact with many different systems in the body depending on the groups attached to the core structure. These pharmacological interactions can include activation of opioid receptors, inhibition of monoamine transporters, and antagonism of glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. NMDA receptor antagonism is part of the dissociative aspect of these compounds but how they affect other receptors is also a factor.

Structures of several compounds related to PCP. Diphenidine is pictured in the bottom row in the middle. From Wallach, et. al., 2016.

Diphenidine interacts with NMDA receptors, serotonin transporter inhibitors, dopamine receptors, and opioid receptors. There have been no human clinical trials for diphenidine so the effects in humans are not well known. Similarity to other substances, such as ketamine, can give some estimation of its effects. Limited toxicity data is available from documented cases of exposure that can also help determine what effects can be expected. Dissociative effects have been reported at lower doses with higher doses causing somatosensory phenomena and transient anterograde amnesia. Reported duration of these effects is about 3-6 hours. Reported adverse effects include hypertension, tachycardia, agitation, muscle rigidity, anxiety, confusion, disorientation, dissociation, and hallucinations.

In one case report, a 30 year-old white male was found confused and agitated by his bed. A small baggie labeled as 1g diphenidine was on the floor nearby. Midazolam was administered by first responders at the scene and on route to the hospital with minimal effect on his mental state. Observed symptoms included increased heart rate (tachycardia), increased respiratory rate (tachypnea), and small (miotic) pupils. Examination at the hospital determined body temperature was slightly elevated at 100.4°F (38.0°C) and metabolic acidosis with a blood pH of 7.17. Normal blood pH is 7.35-7.45. Midazolam, diazepam, chlorpheniramine, haloperidol, and sodium bicarbonate were administered intravenously to sedate him and after 90 minutes, he regained consciousness and did not experience any amnesia. He reported to have taken diphenidine approximately 5 hours prior to being found by first responders. After 12 hours, he was discharged with stable heart rate, stable blood pressure, and normal body temperature.

Diphenidine is not currently scheduled in the United States by the DEA. It is typically sold as a white or yellowish-white powder and consumed by snorting or oral ingestion. It’s marketed as a research chemical and does not have any medical or veterinary use. Because diphenidine exists in a legal gray area, there may be a traceable paper trail, such as records from online vendors and/or bank states documenting its purchase. Additionally, the packaging that it arrives in may be labeled with identifying information.

Axis now screens and confirms for Diphenidine in the 70510 Comprehensive Panel, Blood and Analyte Assurance. For questions about diphenidine or other assistance with interpretation, please call us at 317-759-4869 option 3 or email us at [email protected].

- Wallach J, Kang H, Colestock T, Morris H, Bortolotto ZA, et al. (2016) Pharmacological Investigations of the Dissociative ‘Legal Highs’ Diphenidine, Methoxphenidine and Analogues. PLOS ONE 11(6): e0157021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157021.

- Wink CS, Michely JA, Jacobsen-Bauer A, Zapp J, Maurer HH. Diphenidine, a new psychoactive substance: metabolic fate elucidated with rat urine and human liver preparations and detectability in urine using GC-MS, LC-MSn , and LC-HR-MSn. Drug Test Anal. 2016 Oct;8(10):1005-1014. doi: 10.1002/dta.1946. Epub 2016 Jan 26. PMID: 26811026.

- Gerace E, Bovetto E, Corcia DD, Vincenti M, Salomone A. A Case of Nonfatal Intoxication Associated with the Recreational use of Diphenidine. J Forensic Sci. 2017 Jul;62(4):1107-1111. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13355. Epub 2017 Jun 9. PMID: 28597920.

Recap of Laureen Marinetti NAME & SOFT 2025 Presentations

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Dec 8, 2025 | Announcements, Drug Classes

In October 2025, Laboratory Director and Chief toxicologist Laureen Marinetti, PhD, made presentations at both the National Association of Medical Examiners 2025 Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, and at the Society of Forensic Toxicologists 2025 Conference in Portland, Oregon.

NAME 2025 Recap #1: Propoxyphene

At this year’s NAME meeting, Laureen Marinetti presented Propoxyphene was taken off the Market Fifteen Years Ago, and Yet the Lab is still Confirming it in Toxicology Casework. This presentation was developed in conjuction with her fellow Axis toxicologists, Kevin Shanks and Stuart Kurtz.

Dextro-propoxyphene was introduced for clinical use in 1963 as an opioid pain reliever for mild to moderate pain. It was sold under various names as a single-ingredient product (e.g., Darvon or Wygesic), or as part of a combination product which could contain acetaminophen, aspirin, phenacetin, and/or caffeine (e.g., Darvocet, Darvon Compound-65). The most frequent side effects of propoxyphene include lightheadedness, dizziness, sedation, nausea, and vomiting. However as the drug continued to be used it was discovered that, even during proper therapeutic use, it was cardio-toxic. Taken at therapeutic doses, there were significant changes to the electrical activity of the heart: prolonged PR interval, widened QRS complex and prolonged QT interval. In November of 2010 the FDA released a drug safety communication that recommended against the continued use of dextro-propoxyphene. Levo-propoxyphene (FDA approved in 1962) was available as an antitussive (Novrad) with no opioid like effects, however it was removed from the market in the 1970s. Eight cases confirmed positive for propoxyphene and/or norpropoxyphene in cases received by the lab from January 2020 to April of 2025. The eight cases were from the following States; Arizona (2), Florida (2), Kentucky (1), Michigan (1), and Ohio (2). Since this presentation there has been at least one additional case confirmed. Of these 8 cases there was only one in which propoxyphene may have played a role in the cause of death. This data shows that old drugs should never be counted out. Somehow they have a way of making an appearance just when you thought you would probably never see them again.

References

- Wilsa J. Raymonvil, George Hime, and Diane Moore, “Propoxyphene – Gone but not Forgotten”, Poster 27 presented at the Society of Forensic Sciences annual meeting in St. Louis, MO., 2024.

- Baselt, Randall C., Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 12th Edition, Biomedical Publications, 2020.

NAME 2025 Recap #2: Drug Screening of Vitreous Fluid

Laureen Marinetti presented Case Comparisons of Blood, Vitreous Fluid, and Urine (Where Available): Update: Drug Screen Findings in Over 200 Cases. This presentation was also developed in conjuction with her fellow Axis toxicologists, Kevin Shanks and Stuart Kurtz.

Vitreous fluid is located in the eye between the retina and the lens. It is made up of ~ 99% water but 2 to 4 times more viscous. Vitreous fluid is commonly tested for electrolytes, glucose, creatinine, urea nitrogen, heroin exposure, recent cocaine use, and to help determine the absorption state of ethanol. It can also be tested as a second specimen to confirm drug findings from another matrix. Depending upon the circumstances of a death, vitreous fluid may be the best or only specimen available for toxicology testing. Data regarding the presence and concentration of drugs in vitreous fluid as compared to whole blood is limited. Drug penetration in to vitreous fluid depends on various factors: blood concentration, physicochemical and pharmacological properties, distribution volume, protein binding and blood retinal barrier (BRB) permeability. Drugs may diffuse passively or be actively transported across the BRB. Confirmed drug findings in over 1000 cases (more cases were added after the abstract was turned in to NAME) were compared between blood, vitreous fluid, and urine, where available. These data are important to help determine if a specific drug would be expected to be detected in vitreous fluid. Knowledge of the limitations of using vitreous fluid as a matrix in which to perform general drug screening is necessary for the proper interpretation of the results. Commonly encountered drugs did confirm in vitreous fluid with the exception of cannabinoids. In fact, a lingering opioid death may be able to be determined by comparing blood and vitreous fluid concentrations. Cases involving fentanyl will were presented as examples. Vitreous fluid can be useful in the detection of some drugs but not all drugs. In an acute overdose, drugs may not have had enough time to pass into the vitreous fluid before death occurred, an example of such a case will be presented. Also drugs at lower concentrations in blood may not be detectable in vitreous fluid, as well as those drugs that are lipophilic like benzodiazepines. Vitreous fluid has its place in toxicology testing, however due to its’ limitations, using it as a specimen for general drug screening should be avoided.

References

- Erin B. Divito, Jedediah I. Bondy, Zachary J. DiPerna, Frederick W. Fochtman, and Christopher B. Divito. A comparison of vitreous fluid and blood matrices in postmortem drug analysis, Jrn. of Analytical Toxicol., 2025, Vol 49, 351-357.

- Fabien Be´valot, Nathalie Cartiser, Charline Bottinelli, Laurent Fanton, and Je´roˆme Guitton, Vitreous humor analysis for the detection of xenobiotics in forensic toxicology: a review, Forensic Toxicol., 2015.

- Anna Pelander, Johanna Ristimaa, and Ilkka Ojanperä, Vitreous Humor as an Alternative Matrix for Comprehensive Drug Screening in PostmortemToxicology by Liquid Chromatography–Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry, Jrn. of Analytical Toxicol., 2010, Vol 34, 312-318.

SOFT 2025 Recap: GHB

Laureen Marinetti presented Gamma Hydroxybutyrate: What Does the Concentration Mean? Review of Ante-mortem and Postmortem Casework from 2020 – 2025. Laureen J. Marinetti, Ph.D, F-ABFT, Kevin G. Shanks, M.S., D-ABFT-FT, and Stuart A. K. Kurtz, M.S., D-ABFT-FT. The abstract (S-58) is available upon request.

Gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB) is an endogenous molecule, a prescription drug, an illicit drug, and can be formed both ante-mortem and postmortem, making interpretation difficult. As an endogenous molecule, GHB acts as a neuromodulator with primary activity at the gamma- aminobutyrate B (GABAB) receptor; it is also a minor metabolite of GABA. Clinically, GHB was first used in the 1960s as an adjunct to anesthesia but was unpredictable regarding its duration of effect, likely due to its steep dose response curve. GHB is now used clinically to treat narcolepsy and alcohol withdrawal syndrome. As an illicit drug, GHB can be derived from its precursors, gamma butyrolactone (GBL), and 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BD), both are industrial solvents. GHB can be elevated in blood samples collected in sodium citrate tubes, and GHB can increase postmortem during the decomposition process.

The data reviewed consisted of a total of 402 ante-mortem and postmortem cases sent to the lab that were tested for GHB, either as directed testing or as part of a drug panel. GHB testing in postmortem cases resulted in 20 positive bloods, and 1 positive urine sample, out of 31 cases that were directed for GHB testing. There was a total of 9 ante-mortem blood and urine samples positive for GHB out of a total of 371 cases (2.4%) tested in the drug facilitated assault panel. Selections of these cases were presented.

The Axis cases in which GHB use was suspected were not always the cases with the highest GHB concentration. Review of the literature shows various cut offs proposed for postmortem blood and urine GHB to try to differentiate between endogenous and exogenous GHB. The cut offs vary from 20 to 50 mcg/mL in blood, and 10 to 30 mcg/mL in urine. In the Axis postmortem cases there were 7 blood samples with a GHB of less than 20 mcg/mL, 2 cases less than 30 mcg/mL, and no cases greater than 30 and less than 50 mcg/mL. The concentration range of GHB for all postmortem samples was 6.0 to 1668 mcg/mL. The endogenous GHB cut offs for ante-mortem blood and urine commonly used are 2, and 10 mcg/mL, respectively. In the five Axis ante-mortem blood cases there was a GHB concentration median of 74 and a mean of 59.7 mcg/mL, with a range of 6 to 78.2 mcg/mL. In the four Axis ante-mortem urine positive GHB cases, there were two cases less than 10 mcg/mL, a median of 8.7 and a mean of 11.7 mcg/mL, with a range of 7.5 to 248 mcg/mL.

In a 2025 study of 525 cases where no exogenous GHB use was suspected, 85% of the cases showed evidence of GHB formation postmortem, with a urine/blood ratio median of 0.52. Postmortem GHB in blood was usually less than 50 mcg/mL, but not always, 30% were above 50 mcg/mL. It was proposed that a urine/blood ratio of greater than 2.0 suggested exogenous use of GHB, however 15% of these cases had blood GHB of less than 50 mcg/mL. It was also suggested that a longer post mortem interval (PMI) resulted in a greater chance of GHB formation postmortem (Arnes et. al. 2025).

Interpretation of GHB in postmortem blood can be problematic. A detailed history and the ability to test additional specimens such as urine and vitreous fluid may be necessary.

References

- Marit Arnes, Hilde Marie Eroy Edvardsen, Line Berge Holmen, Lena KIristoffersen, and Gudrun Hoiseth, Post-mortem formation of GHB: A retrospective study of forensic autopsies, Forensic Science International 2025, 372.

- Jennifer L. Smith, Shaun Greene, David McCutcheon, Courtney Weber, Ellie Kotkis, Jessamine Soderstrom, et.al., A multicentre case series of analytically confirmed gamma-hydroxybutyrate intoxications in Western Australian emergency departments: Pre-hospital circumstances, co-detections and clinical outcomes, Drug and Alcohol Review, 2024; 1-13.

- A.W. Jones, A. Holmgren F.C., Kugelberg, and F.P. Busardò, Relationship Between Postmortem Urine and Blood Concentrations of GHB Furnishes Useful Information to Help Interpret Drug

- Intoxication Deaths, Journal of Analytical Toxicol, 2018, Vol 42, 587-591.

Recap of Stuart Kurtz NAME & SOFT 2025 Presentations

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Nov 19, 2025 | Announcements, Drug Classes

In October 2025, toxicologist Stuart Kurtz made presentations at both the National Association of Medical Examiners 2025 Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, and at the Society of Forensic Toxicologists 2025 Conference in Portland, Oregon.

NAME 2025 Recap: Nitazenes

At this year’s NAME meeting, Stuart Kurtz presented a poster titled A Review of Cases Involving Nitazenes. This poster was in collaboration with the Kentucky State Medical Examiner’s Office, and Axis would like to thank them for their contributions.

Nitazenes were synthesized and studied as veterinary anesthetics with etonitazene as the 1st compound in 1957. None of the originally studied nitazenes were approved for veterinary purposes and no human clinical trials were performed. Isotonitazene emerged in illicit drug markets in 2019 and several nitazenes have emerged since then including N-pyrrolidino derivatives which were not described in original drug patents.

Axis uses liquid chromatography paired with quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (LC-QToF-MS) for screening and liquid chromatography paired with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for confirmation. Nitazenes don’t have any known stability issues that impact short-term storage and testing. Routine sampling techniques and preservative-containing containers are sufficient for toxicology testing.

In the cases examined, 9 had a history of suspected drug use noted and 1 case (Case 5) was noted as ruling out OD vs. drowning. Cases 4 & 6 had no other significant findings. Cases 2 & 8 had a designer benzodiazepine present but no other drugs of significance. Designer benzodiazepines are not typically the sole drug found in drug-related deaths. Often times, they are detected with a stimulant or opioid in postmortem casework.

If you would like a copy of the poster or have any questions about this poster or nitazenes in general, please email [email protected].

- Sara E Walton, Alex J Krotulski, Barry K Logan, A Forward-Thinking Approach to Addressing the New Synthetic Opioid 2-Benzylbenzimidazole Nitazene Analogs by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry (LC–QQQ-MS), Journal of Analytical Toxicology, Volume 46, Issue 3, April 2022, Pages 221–231, https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkab117

- Stuart A. K. Kurtz, MS, Kevin G. Shanks, MS, D-ABFT-FT, Dr. Laureen J. Marinetti, Ph.D., F-ABFT, A Look at Nitazenes Our Lab Has Detected Across the Country from 2020-2024, American Academy of Forensic Sciences Annual Meeting 2025, Balitmore, MD

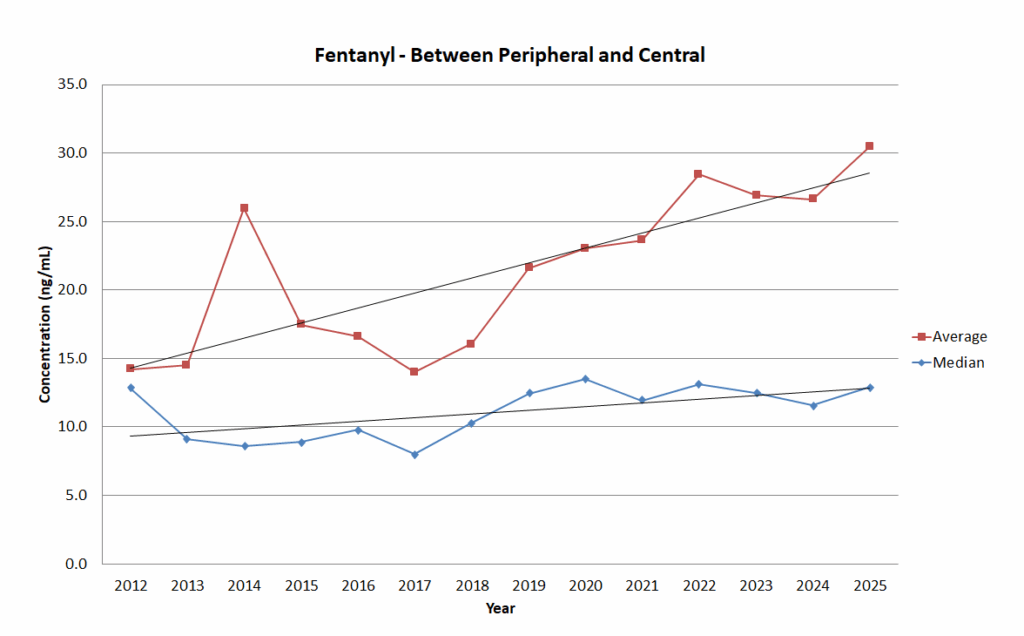

SOFT 2025 Recap: Fentanyl Concentrations

At this year’s Society of Forensic Toxicologists meeting, Stuart Kurtz presented a poster titled The Line Goes Up?: Examining Fentanyl Concentrations Over the Years. The goal of this project was to evaluate, at a zoomed-out look, whether Axis data followed the same trends observed from other labs.

Fentanyl has been the primary opioid in opioid-related deaths for many years now. Publications show labs experiencing an increase in fentanyl concentrations in both human performance and postmortem casework. An overlap in fentanyl concentrations between those areas has been observed for many years. The increase in concentrations could be due to an increase in population tolerance and/or from public health initiatives to raise awareness of the dangers of fentanyl in drugs purchased on the street and the use of naloxone to reverse overdoses.

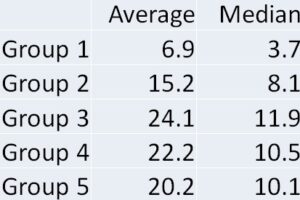

The data was split into 5 groups to represent, as best as possible, the different collection sites used in postmortem casework. These groups include identifiers on the requisition form that the lab records when cases are received.

Group 1: Antemortem – hospital, ER, serum, or whole blood.

Group 2: Peripheral – femoral or peripheral (noted by submitting investigator).

Group 3: Between Peripheral and Central – subclavian, iliac, carotid, or jugular.

Group 4: Central – central, abdominal, heart, IVC, SVC, aorta, cavity, pleural, cardiac, or spleen.

Group 5: Uncategorized – arterial, autopsy, blood clot, inguinal, mixed, subdural, or not indicated.

The aim of splitting the groups was to help account for postmortem redistribution that occurs in all cases. This can lead to much higher concentrations in central sources vs. peripheral sources. Postmortem redistribution doesn’t affect each case equally but does happen in every postmortem case.

The overall trend of the data was that each group increased over time for the mean concentration. The median concentration increased for all groups except Group 1 but one thing that can account for this was the lowering of our screen and confirmation cutoff in 2020. This is consistent with the observations from other labs who have analyzed this trend.

Trend graph for Group 3: Between Peripheral and Central.

This data set had almost 50,000 cases, and Axis would like to thank all of its client offices for their partnership. If you have any questions about this post, need help interpreting fentanyl results for another case, or to request a copy of the poster, please reach out to us via phone at 317-759-4869 option 3 or via email at [email protected].

- Jocelyn Martinez, Jennifer Gonyea, M Elizabeth Zaney, Joseph Kahl, Diane M Moore, The evolution of fentanyl-related substances: Prevalence and drug concentrations in postmortem biological specimens at the Miami-Dade Medical Examiner Department, Journal of Analytical Toxicology, Volume 48, Issue 2, March 2024, Pages 104–110, https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkad089

- Vanessa Havro, Nicholas Casassa, Kevin Andera, Dani Mata, A Two-Year Review of Fentanyl in Driving under the Influence and Postmortem Cases in Orange County, CA, USA, Journal of Analytical Toxicology, Volume 46, Issue 8, October 2022, Pages 875–881, https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkac030

- Ayako Chan-Hosokawa, Jolene J Bierly, 11-Year Study of Fentanyl in Driving Under the Influence of Drugs Casework, Journal of Analytical Toxicology, Volume 46, Issue 3, April 2022, Pages 337–341, https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkab049

A Case of Drug Reemergence: The Synthetic Cannabinoid, 5F-ADB

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Nov 7, 2025 | Drug Classes

By Kevin Shanks, D-ABFT-FT

It has been a little over 4 years since Axis mentioned synthetic cannabinoids on this blog. So, briefly, synthetic cannabinoids are man-made compounds that bind to cannabinoid receptors 1 (CB1) and 2 (CB2) in the body and mediate effects of the endocannabinoid receptor system. While delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive cannabinoid found in cannabis, is a partial agonist of the cannabinoid receptors, most synthetic cannabinoids are full agonists at the same receptors. Synthetic cannabinoids are comprised of many structural variants, which change over time as compounds are controlled by Federal and state governments. Synthetic cannabinoids have been implicated in several outbreaks of illnesses and hospitalizations in the USA as well as associated with cause of death in postmortem toxicology.

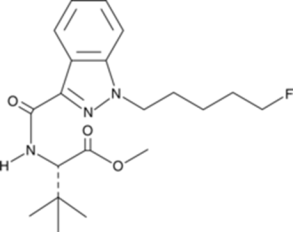

Chemical Structure of 5F-ADB Drawn by Kevin G. Shanks (2025)

Methyl-2-[1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamido]-3,3-dimethylbutanoate, also known as 5F-ADB or 5F-MDMB-PINACA, is a potent synthetic cannabinoid compound that first emerged in Japan in late 2014 when it was identified on plant material products. Synthetic cannabinoids are commonly sprayed on plant material or soaked into small pieces of paper. 5F-ADB’s molecular formula is C20H28FN3O3 and its molecular weight is 377.4 g/mol. 5F-ADB is of the indazole-3-carboxamide family of compounds and consists of an indazole core structure, a fluorinated pentyl chain, and a carboxamide linking group. Common adverse effects after consumption of the substance include psychomotor agitation, tachycardia, confusion, anxiety, and loss of consciousness, psychosis, and fatality.

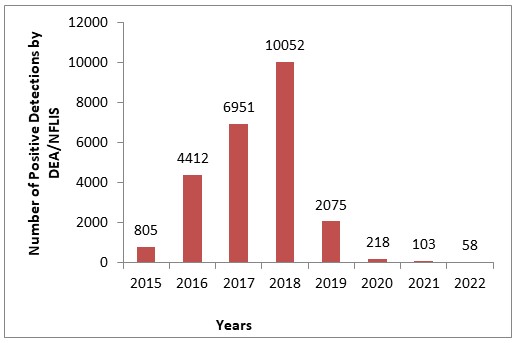

5F-ADB Detections by US DEA Reported in NFLIS Annual Drug Reports (2015-2022)

The drug was first reported by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 2014 and emerged in toxicology testing in 2015. It was made a Schedule I controlled substance in the USA in 2017. After emergence, 5F-ADB hit peak prevalence in 2018 and then rapidly disappeared from the illicit drug market with just a handful of reports by the DEA by 2022. During 2021-2022, Axis Forensic Toxicology had zero detections of 5F-ADB in postmortem toxicology testing. Because of the combined DEA and Axis data, the lab decided to remove it from the scope of synthetic cannabinoid testing in 2022.

Until recently, the compound was considered to be non-existent on the street, but new reports suggest 5F-ADB has made a comeback as one of the top synthetic cannabinoids of choice in the USA. Published reports from NPS Discovery and the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education (CFSRE) in 2025 detail 5F-ADB’s comeback as either the first or second most identified synthetic cannabinoid in cases sent to them. Axis Forensic Toxicology has also spoken to pathologists who have had positive casework for 5F-ADB, over the last few months, especially in the prison population. Because of these recent events, the lab has added 5F-ADB back into the screening scope of analysis in the comprehensive panel (order code 70510). 5F-ADB is rapidly metabolized/degraded to its 3,3-dimethylbutanoic acid metabolite by enzymes in the blood and therefore must be analyzed by monitoring the metabolic product. The reporting limit for 5F-ADB 3,3-dimethylbutanoic acid on the screening test is 2 ng/mL. The result is reported as qualitative. Instrumentation used for analysis is liquid chromatography with quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (LC-qToF-MS). Upon publication of this blog post, Axis has had recent detections of 5F-ADB via its metabolite in 5 different states – Florida, Indiana, Missouri, Ohio, and South Dakota.

It is important to remember that while most novel psychoactive substances emerge and then disappear rapidly from the illicit market, some persist for months and years. And in the case of 5F-ADB, it emerged, peaked, rapidly disappeared, and now has made a resurgence years later. As a toxicology laboratory, it is prudent to monitor the ever-changing scope of the drug market and adapt testing panels accordingly. The current scope of testing offered by Axis Forensic Toxicology can be found in the online test catalog at https://axisfortox.com. As always, if you have questions about 5F-ADB or any other synthetic cannabinoid substances and how they may play a role in your medical-legal investigation, please reach out to our subject matter experts by email ([email protected]) or phone (317-759-4869, Option 3).

References

- Synthetic Cannabinoids. Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Twelfth Edition. Randall C. Baselt. Biomedical Publications. Pages 1979-1986. (2020).

- Tetrahydrocannabinol. Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Twelfth Edition. Randall C. Baselt. Biomedical Publications. Pages 2041-2045. (2020).

- Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists. Novel Psychoactive Substances: Classification, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Paul Dargan and David Wood. Academic Press (Elsevier). 317-338. (2013).

- NPS Discovery and CFSRE Trend Reports, Q1-Q3, 2025.

- Axis Forensic Toxicology. Laboratory Data. Indianapolis, IN. (accessed October 2025).

Recap of Kevin Shanks NAME & SOFT 2025 Presentations

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Nov 6, 2025 | Announcements, Drug Classes

In October 2025, toxicologist Kevin Shanks made presentations at both the National Association of Medical Examiners 2025 Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, and at the Society of Forensic Toxicologists 2025 Conference in Portland, Oregon.

NAME 2025 Recap: MDMB-4en-PINACA

At this year’s NAME meeting, Kevin Shanks presented a poster about the prevalence of the synthetic cannabinoid, MDMB-4en-PINACA, and its detection via the butanoic acid metabolite in postmortem toxicology cases. Axis has previously discussed synthetic cannabinoids on this blog, but briefly, synthetic cannabinoids are synthetically derived substances designed to simulate the effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Unlike natural cannabinoids found in the cannabis plant, synthetic cannabinoids are often created in clandestine laboratories and sold as herbal incense, powders, or vape liquids. These compounds are full agonists of the cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2) and produce effects more intense than cannabis, which can include anxiety, agitation, tachycardia, hypertension, paranoia, hallucinations, seizure, and death.

MDMB-4en-PINACA is an older synthetic cannabinoid compound and was first detected in the USA in 2019. Even though it was federally scheduled in 2023, it has remained as one of the top two most prevalent synthetic cannabinoids in the USA. Because MDMB-4en-PINACA is subject to rapid enzymatic degradation in blood, Axis analyzes for the compound via its 3,3-dimethylbutanoic acid metabolite. Axis’ analytical methods screen for MDMB-4en-PINACA butanoic acid metabolite by liquid chromatography with quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (LC-qToF-MS) and confirm by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Results are reported qualitatively and the limit of detection is 2 ng/mL.

From 1/1/2024 to 3/31/2025, the lab reported 126 detections of MDMB-4en-PINACA butanoic acid metabolite in postmortem casework. The substance was detected in 10 states (Indiana, Florida, Kentucky, Kansas, Michigan, Missouri, Illinois, Nebraska, Ohio, and Louisiana) with the vast majority of positive results from Indiana (64 cases). The substance was the sole compound of toxicological relevance in 29 cases. In the other 97 cases, the most prevalent compounds detected alongside the synthetic cannabinoid were fentanyl (32 cases), methamphetamine (32 cases), cocaine/benzoylecgonine (15 cases), and ethanol (14 cases).

While MDMB-4en-PINACA is several years old, it is still prevalent in postmortem toxicology casework and its popularity has not been affected by governmental scheduling. It is important to remember that some older novel psychoactive substances may stick around much longer than is normal and it is prudent to be aware of those substances and how they may play a role in a medical-legal death investigation. To discuss the potential impact of synthetic cannabinoids in your casework or for more information about the presentation, please contact [email protected]

SOFT 2025 Recap: Phencyclidine (PCP)

At this year’s SOFT meeting, Kevin Shanks presented a poster about the detection and prevalence of phencyclidine (PCP) in postmortem toxicology casework.

PCP was first synthesized in 1926 and its use as an anesthetic was discovered in 1956. Shortly thereafter, PCP was allowed as a medication as a short-acting anesthetic in humans, but quickly was removed from the market after adverse effects were observed. PCP appeared on the illicit drug market in the USA in 1967 and became a drug of abuse throughout the 1970s-1980s. It is typically used orally, insufflated, smoked, or injected intravenously. Pharmacologically, PCP is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist and it has cholinergic, adrenergic, and dopaminergic effects. Physiological effects include hypertension, hyperthermia, perspiration, hyper salivation, repetitive motor movements, muscle rigidity, arrhythmia, and seizure. Psychological effects include agitation, anxiety, dissociation, insomnia, rage, amnesia, and catatonia.

Axis’ analytical methods screen for PCP by liquid chromatography with quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (LC-qToF-MS) and confirm by gas chromatography with mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Results are reported quantitatively and the reporting limit is 50 ng/mL. From 1/1/2023 to 5/1/2025, Axis detected PCP in 83 postmortem blood toxicology cases. The substance was detected across 8 states (Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, and Texas) with the majority of detections being from Missouri (73.4%). PCP was the sole substance of toxicological interest in 16 cases; PCP blood concentrations averaged 313 ng/mL in these cases. The most common substances detected alongside PCP were cocaine, ethanol, fentanyl, methamphetamine, and THC; and in those cases, PCP blood concentrations were generally lower than those cases where PCP was detected alone.

While most of the focus in postmortem toxicology presently is centered on fentanyl and novel psychoactive substances, it is important to remember that older, more classical drugs of abuse still exist. It is prudent that the postmortem toxicology laboratory include them in every comprehensive toxicology analysis. If you have a PCP-related question or more information about the presentation, please do not hesitate to reach out to our subject matter experts at [email protected].

Read MoreDrug Primer: 7-OH Mitragynine

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Oct 17, 2025 | Drug Classes

By Stuart Kurtz, D-ABFT-FT

Axis Forensic Toxicology has previously written on kratom and cases involving kratom fatalities. As a quick recap, Mitragyna speciosa, is a tree or shrub that grows in southeast Asia. It’s part of the Rubiaceae family which includes coffee plants. It can be consumed by chewing leaves, brewing a beverage, or pulverized and smoked or put in a capsule. Fatalities have been reported from kratom use with mitragynine as the primary alkaloid responsible for toxic effects.

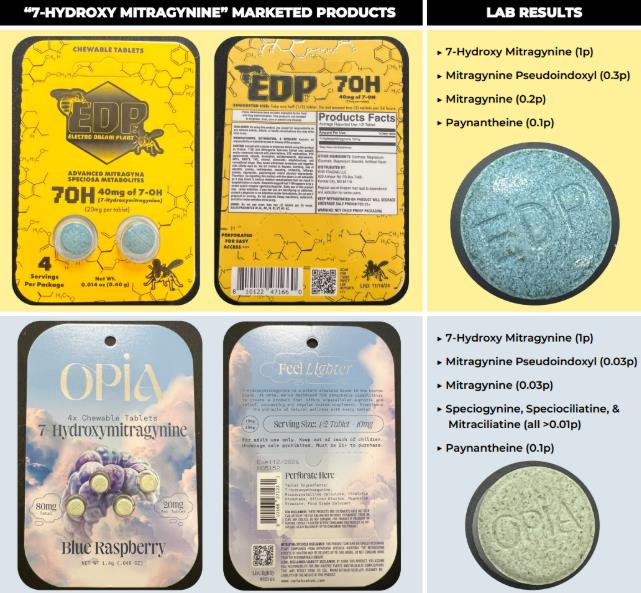

7-OH mitragynine is naturally occurring in the kratom plant at about 2% of the alkaloid content and is 10 times more potent than mitragynine. Reported side effects include agitation, nausea, vomiting, confusion, seizures, and fast heart rate. Due to activity at the mu opioid receptor, the receptor primarily associated with opioids such as fentanyl and morphine, severe cases can present similar to opioid overdoses. 7-OH mitragynine is further metabolized into mitragynine pseudoindoxyl which is 100 times more potent than mitragynine. Mitragynine pseudoindoxyl is also found in the kratom plant in low concentrations. Labs that test for mitragynine may not currently be testing for 7-OH mitragynine. Historically, the concern with kratom related toxicity has been centered on testing for mitragynine since that was the primary alkaloid in kratom products. However, new products may contain higher amounts of 7-OH mitragynine and/or mitragynine pseudoindoxyl and low or no amount of mitragynine which investigators and labs should be aware of moving forward with these cases.

Image from United States Food and Drug Administration showing 7-OH mitragynine extract (left), powder (middle), and gummies (right).

7-OH mitragynine products are manufactured by converting mitragynine in the kratom plant to 7-OH mitragynine. Available products containing primarily 7-OH mitragynine include concentrates, edibles, extracts, beverages, and tablets for chewing or swallowing. Testing of these products shows that they are primarily 7-OH mitragynine with a variable amount of unconverted mitragynine and other products that could be related to the synthesis process. These can often be found in stores that also sell kratom products and lead to confusion as to what the buyer is actually getting. Given the increase in potency of 7-OH mitragynine compared to mitragynine, the primary alkaloid in kratom, a naïve user may experience a toxic event if they are expecting the product to behave like kratom.

Image from United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Laboratory and Scientific Services Portal showing 7-OH mitragynine tablets and testing results of the contents.

Interpretation can be tricky when it comes to mitragynine presence. It can be associated with kratom use or synthesis of mitragynine to produce the more potent 7-OH mitragynine instead of, or in addition to, mitragynine. A good indicator will be what products are found at the scene and if they are consistent in how they are labeled between products. A product labeled as kratom or mitragynine may actually be a 7-OH mitragynine product especially since the FDA is currently in the process of scheduling mitragynine only, which may lead to more products containing 7-OH mitragynine to avoid legal issues. Therefore, testing for both mitragynine and 7-OH mitragynine will be useful. Axis recommends that you check the testing scope with your lab to see if they test for one, both, or neither of these compounds. Axis currently screens with LC-QToF-MS for mitragynine and 7-OH mitragynine in our 70510 Comprehensive Panel with Analyte Assurance. Confirmation of mitragynine is quantitative using LC-MS/MS and 7-OH mitragynine is qualitative using LC-QToF-MS.

If you have any questions regarding this or other topics, please reach out to us via email [email protected] or call at 317-759-4869 option 3.

Krotulski, AJ; Denn, MT; Brower, JO; Papsun, DM; Logan, BK. (2025), Evaluation of Commercially Available Smoke Shop Products Marketed as “7-Hydroxy Mitragynine” & Related Alkaloids, Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, United States.

Anderer S. What to Know About 7-OH, the New Vape Shop Hazard. JAMA. 2025;334(12):1045–1046. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.13592

Smith, K.E., Boyer, E.W., Grundmann, O., McCurdy, C.R. and Sharma, A. (2025), The rise of novel, semi-synthetic 7-hydroxymitragynine products. Addiction, 120: 387-388. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16728

Pullman MK, Kanumuri SRR, Leon JF, Cutler SJ, McCurdy CR, Sharma A. Cardio-pulmonary arrest in a patient revived with naloxone following reported use of 7-hydroxymitragynine. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2025 Sep 30:1-2. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2025.2565428. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41025553.

Read MoreAxis Adds Analytes to our Comprehensive Panel with Analyte Assurance™

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Sep 17, 2025 | Announcements

We’re pleased to inform you that our Comprehensive Panel with Analyte Assurance™, along with the referenced panels below, will be updated for all orders effective September 29, 2025. The following analytes will be added:

- 5F-ADB Butanoic Acid Metabolite – Confirmed via Synthetic Cannabinoids Panel

- 7-Hydroxymitragynine – Confirmed via Novel Emerging Compounds Panel

- MDPHP – Confirmed via Novel Emerging Compounds Panel

- BTMPS – Confirmed via Novel Emerging Compounds Panel

- Diphenidine – Confirmed via Novel Emerging Compounds Panel

As with all components of Analyte Assurance™, if any of these analytes screen positive, our Lab Client Support team will contact you directly to determine whether confirmatory testing is desired.

At Axis Forensic Toxicology, we are committed to evolving with the needs of our clients and the ever-changing landscape of emerging substances. These additions reflect our proactive approach to ensuring you receive the most comprehensive and reliable testing services available.

If you have any questions or would like more information regarding this update, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us at [email protected]. Our team is always ready to assist.

Thank you for your continued partnership and trust in Axis. We look forward to continuing to support your work with the highest quality service and testing solutions.

Sincerely,

Matt Zollman

Director of Operations & Product Management

The Utility of Drug Testing in Urine

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Sep 2, 2025 | General

By Laureen Marinetti, PhD, F-ABFT

As part of its whole case approach, Axis Forensic Toxicology includes urine drug testing alongside blood testing in both the Comprehensive Panel with Analyte Assurance™ and Drugs of Abuse Panel. The standard urine screen typically covers common drugs of abuse, excluding barbiturates and cannabinoids—though these can be added upon request.

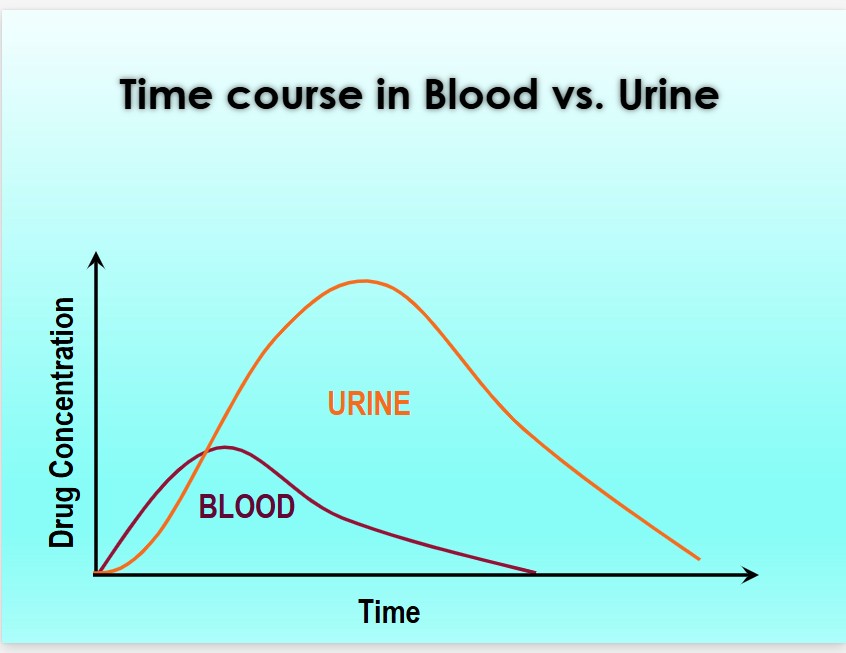

Urine often contains higher concentrations of drugs and metabolites than blood, and substances may remain detectable in urine for days or longer after use.

From The Society of Forensic Toxicologists (SOFT) Drug-Facilitated Crime Committee. PowerPoint DFSA, DFCC 2017

The primary value of urine drug findings lies in their ability to reveal past drug use. Historical drug use may or may not be relevant to a case. For instance, blood results may show no detectable levels of stimulants such as cocaine or methamphetamine, while urine results are positive—indicating prior use. This information could be significant if the decedent had underlying cardiac disease.

In another scenario, urine results may suggest illicit drug use even when blood results are negative. This can help establish a timeline of drug use or corroborate blood findings. However, the concentration of drugs in urine is generally not useful for determining prior blood levels or the timing of drug use.

Quantitative urine values are only meaningful in specific contexts—such as when extensive comparative data to blood exists (e.g., ethanol), or when distinguishing endogenous from exogenous exposure (e.g., GHB). Axis provides urine concentration data only when it offers interpretive value.

In summary, Axis Forensic Toxicology incorporates urine drug testing alongside blood analysis to provide a more complete picture in forensic investigations. Urine testing is particularly valuable for detecting past drug use, as many substances remain in urine longer and at higher concentrations than in blood. While urine results cannot determine the timing or quantity of drug use, they can offer critical context—especially in cases involving underlying health conditions or suspected substance abuse. Quantitative urine data is only reported when it has clear interpretive value. As always, please do not hesitate to contact Axis Forensic Toxicology with any questions, concerns, or for assistance with case interpretation. Our team is committed to supporting your investigative needs with accurate and insightful toxicological analysis and interpretation.

Read More4-ANPP in Biological vs. Non-Biological Samples: The Interpretation is not the Same

by Denise Purdie Andrews | Aug 8, 2025 | Drug Classes

By Kevin Shanks, M.S., D-ABFT-FT

We have previously discussed both fentanyl and 4-ANPP in this blog (1-2), but briefly, fentanyl is a mu opioid receptor agonist that is used as both a pharmaceutical medication and as an illicit drug found on the street typically as a powder or tablet. Fentanyl itself is metabolized primarily by the CYP3A4 enzyme in the human body. It can be dealkylated, hydroxylated, methylated, and hydrolyzed (3-4). At Axis, we monitor for the presence of the unchanged drug, fentanyl, alongside its primary metabolite, norfentanyl, in blood and urine. Several years ago, we added a second fentanyl-related substance to the scope of testing – 4-ANPP.

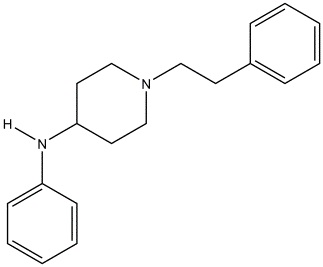

Chemical structure of 4-ANPP

Drawn by Kevin G. Shanks (2022)

So, what is 4-ANPP? The substance is known chemically as N-phenyl-1-(2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidinamine, but is also referred to as despropionyl fentanyl. It is formed via amide hydrolysis of the parent substance. It is considered to be a minor inactive metabolite of fentanyl – meaning it does not produce a pharmacological effect on the body (5-6). But it is also a precursor or starting material used in the synthesis of illicitly manufactured fentanyl and various related fentanyl derivatives or analogs. As an example, 4-ANPP can be reacted with propionyl anhydride to form fentanyl or acetic anhydride to form acetylfentanyl. 4-ANPP is not used in the synthesis of pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl.

Why is all of this important? The presence of illicitly manufactured fentanyl in the street drug supply in the USA has rapidly increased over the past 10-12 years (7). And with that increased presence comes a large increase in overdose deaths due to the substance. Recent CDC data shows that over 100,000 people died yearly from drug overdoses in the USA in 2022-2024, with the major driving factor being the prevalence of illicit fentanyl in the street drug supply (8).

Ultimately, the presence of 4-ANPP in a biological specimen such as blood or urine is merely a marker for fentanyl use or exposure. The product used may have been either pharmaceutical fentanyl or illicitly manufactured fentanyl. The origin of the fentanyl – pharmaceutical vs. street – cannot be determined by the toxicology results alone. In order to ascertain if 4-ANPP is present in the body from metabolism or if it was ingested by using an impure illicit street product, testing must be conducted on evidence from the scene which may include unidentified powders or tablets. If 4-ANPP is detected in the non-biological evidence, then it may be determined that the fentanyl exposure is from a non-pharmaceutical origin.

Axis Forensic Toxicology tests for the presence of 4-ANPP in our Comprehensive Drug Panel with Analyte Assurance™, Blood (order code 70510), which is completed by liquid chromatography with quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (LC-QToF-MS) and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The reporting limit is 100 pg/mL and the substance is reported as qualitatively positive or negative – it is not reported quantitatively.

If you have any questions regarding the presence or absence of 4-ANPP or its role in your toxicology casework, please reach out to Axis’ subject matter experts at [email protected].

References

- Drug Primer: Fentanyl (2021). Axis Forensic Toxicology Blog. Drug Primer: Fentanyl – Axis Forensic Toxicology (axisfortox.com).

- Drug Primer: 4-ANPP (2022). Axis Forensic Toxicology Blog. Drug Primer: 4-ANPP – Axis Forensic Toxicology (axisfortox.com).

- Fentanyl. Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Twelfth Edition. Randall C. Baselt. Biomedical Publications. Pages 844-847. (2020).

- Opioids. Principles of Forensic Toxicology. Fourth Edition. Barry Levine. AACC, Inc. Pages 271-291 (2017).

- Labroo, R.B., Paine, M.F., Thummel, K.E., Kharasch, E.D. (1997) Fentanyl Metabolism by Human Hepatic and Intestinal Cytochrome P450 3A4: Implications for Interindividual Variability in Disposition, Efficacy, and Drug Interactions. Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 25: 9. 1072-1080.

- Wilde, M., Pichini, S., Pacifici, R., Tagliabracci, A. et al. (2019) Metabolic Pathways and Potencies of New Fentanyl Analogs. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 10: 238. 1-16.

- 2022 Annual Drug Report. National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS). Drug Enforcement Administration. Springfield, VA.

- Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. National Vital Statistics System. Center for Disease Control. Vital Statistics Rapid Release – Provisional Drug Overdose Data. (Accessed 07/31/2025).